Sanggar Kegiatan Belajar Berada Pada Posisi Yang Lemah Dalam Hukum

Sanggar Kegiatan Belajar (SKB) dilahirkan tahun 1978 memiliki posisi hukum yang kalah kuat dibanding dengan Pusat Kegiatan Belajar Masyarakat (PKBM) yang baru lahir dua puluh tahun kemudian.

Memperkenalkan Daerah dengan mengenakan Baju Adat di Apresiasi PTKPAUDNI 2013

Go to Blogger edit html and find these sentences.Now replace these sentences with your own descriptions.This theme is Bloggerized by Lasantha Bandara - Premiumbloggertemplates.com.

This is default featured slide 3 title

Go to Blogger edit html and find these sentences.Now replace these sentences with your own descriptions.This theme is Bloggerized by Lasantha Bandara - Premiumbloggertemplates.com.

Pendidikan Luar Sekolah

Pendidikan Luar Sekolah adalah pendidikan yang memberdayakan masyarakat dan membantu menyelesaikan masalah dari potensi SDM yang ada.

This is default featured slide 5 title

Go to Blogger edit html and find these sentences.Now replace these sentences with your own descriptions.This theme is Bloggerized by Lasantha Bandara - Premiumbloggertemplates.com.

Sabtu, 28 Juni 2014

Hasil polling mulai tanggal 10 Juni s.d. 24 Juni 2014

Senin, 09 Juni 2014

Selasa, 13 Mei 2014

Kamis, 31 Oktober 2013

Progres Pengembangan Kurikulum Nasional Berbasis KKNI Jurusan/Prodi PLS

Minggu, 27 Oktober 2013

Welcome Nonformal Education Practitioners

Terima kasih sudah berkesempatan mengunjungi kami. tanpa mengurangi rasa hormat kami atas dukungan, saran, kritik serta masukan-masukan anda yang membangun kami mengajak anda untuk kami perkenalkan sedikit mengenai Pendidikan Nonformal.

Undang-undang Sistem Pendidikan Nasional No. 20 Tahun 2003 menyatakan bahwa sistem pendidikan di Indonesia terdiri atas 3 jalur yaitu Pendidikan Formal, Pendidikan Nonformal dan Pendidikan Informal.

Beberapa permasalahan yang masih dihadapi dalam penyelenggaraan pendidikan nonformal dewasa ini guna meningkatkan kapasitas tersebut penelitian dan pengembangan pendidikan nonformal yang terintegrasi serta dalam meningkatkan kepedulian masyarakat di bidang pemberdayaan masyarakat diperlukan suatu wadah yang diharapkan dapat menjadi sarana penyampaian informasi, komunikasi, dan diskusi antar peneliti pendidikan nonformal, sehingga diharapkan akan muncul suatu sinergi dalam pengembangan agen pembaharuan pendidikan nonformal di Indonesia. Organisasi tersebut bersifat ilmiah, terbuka, dan independen, memiliki soliditas dan komitmen tinggi untuk menggalang kekuatan ilmiah, lembaga perguruan tinggi, lembaga penelitian, pemerintah dan industri pendidikan untuk mengembangkan pendidikan nonformal sebagai strategi rasional dalam upaya pengembangan agen pembaharuan pendidikan nonformal di Indonesia. Didorong oleh tekad tersebut, maka dengan memohon Rahmat dan Ridha Tuhan Yang Maha Esa, dibentuk Nonformal Education Research & Consultant Indonesia (NFERCI)

Cara membuat Blog di Blogger

Pada awalnya, blog dibuat adalah sebagai catatan pribadi yang disimpan secara online, namun kini isi dari sebuah blog sangat bervariatif ada yang berisi tutorial ( contoh blog ini ), curhat, bisnis dan lain sebagainya. Secara umum, blog tidak ada bedanya dengan website pada umumnya yang ada di internet.

Flatform blog atau seringkali disebut dengan mesin blog dibuat sedemikian rupa oleh para designer/programer penyedia blog agar mudah untuk digunakan. Dulu, untuk membuat aplikasi web diperlukan pengetahuan tentang pemrograman HTML, PHP, CSS dan lain sebagainya, dengan blog semuanya menjadi mudah semudah menyebut angka 1 2 3.

Cara membuat Blog di Blogger

Salah satu penyedia blog gratis yang cukup populer saat ini adalah blogspot atau blogger, dimana ketika mendaptar adalah melalui situs blogger.com namun nama domain yang akan anda dapatkan adalah sub domain dari blogspot, contoh : contohsaja.blogspot.comKenapa harus membuat blog di blogger.com bukan pada situs penyedia blog lainnya? Sebenarnya tidak ada keharusan untuk membuat blog di blogger, namun ada banyak kelebihan yang dimiliki blogger di banding dengan penyedia blog lain. Beberapa contoh kelebihan blogger di banding yang lain yaitu mudah dalam pengoperasian sehingga cocok untuk pemula, lebih leluasa dalam mengganti serta mengedit template sehingga tampilan blog anda akan lebih fresh karena hasil kreasi sendiri, custom domain atau anda dapat mengubah nama blog anda dengan nama domain sendiri misalkan contohsaja.blogspot.com di ubah menjadi contohsaja.com,sedangkan hosting tetap menggunakan blogspot dan masih tetap gratis.

Perlu ditekankan dari awal bahwa internet itu sifatnya sangat dinamis, sehingga mungkin saja dalam beberapa waktu kedepan panduan membuat blog di blogger ini akan sedikit berbeda dengan apa yang anda lihat di blogger.com

Untuk mengurangi hal yang tidak perlu di tulis, berikut cara membuat blog di blogger.com

Membuat Email

Salah satu syarat yang harus dipenuhi dalam membuat blog adalah anda memiliki alamat email yang masih aktif atau di gunakan. Jika anda belum mempunyai alamat email, silahkan daftar terlebih dahulu di gmail karena blogger adalah salah satu layanan dari Google maka ketika mendaftar ke blogger sebaiknya gunakan email gmail. Jika anda belum paham bagaimana cara membuat email, silahkan baca terlebih dahulu postingan cara membuat email gmail.Daftar Blog di blogger

- Silahkan kunjungi situs http://www.blogger.com

- Setelah halaman pendaftaran terbuka, alihkan perhatian ke sebelah

kanan bawah, ubah bahasa ke Indonesia agar lebih mudah difahami.

- Silahkan langsung masuk/login dengan menggunakan username/nama pengguna serta password/sandi gmail anda ( akun email anda bisa untuk login ke blogger).

- Isilah formulir yang ada :

- Nama tampilan : isi dengan nama yang ingin tampil pada profile blog anda.

- Jenis Kelamin : pilih sesuai dengan jenis kelamin anda, misal : pria.

- Penerimaan Persyaratan : Beri tada ceklis sebagai tanda anda setuju dengan peraturan yangtelah di tetapkan oleh pihak blogger. Saran: sebaiknya anda membaca terlebih dahulu persyaratan yang ada agar anda tahu dan mengerti apa yang boleh dan tidak diperbolehkan ketika menggunakan layanan blogger.

- Klik tanda panah bertuliskan “Lanjutkan”.

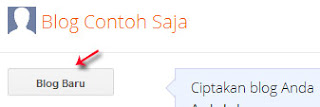

- Klik tombol “Blog Baru”.

- Isilah formulir :

- Judul : Isi dengan judul blog yang di inginkan, misal : Coretan sang penghayal

- Alamat : isi dengan alamat blog yang di inginkan. Ingat! Alamat ini tidak dapat di edit kembali setelah dibuat, apabila anda ingin serius, maka pilihlah nama yang benar-benar anda inginkan.

- Template : pilih template (tampilan blog) yang disukai (ini dapat ganti kembali).

- Lanjutkan dengan klik tombol “Buat blog!”.

- Sampai disini blog anda telah berhasil di buat.

- Untuk menghindari spam filter, sebaiknya anda langsung posting sembarang saja. Klik tulisan “Mulai mengeposkan”.

- Isi judul serta artikel. Akhiri dengan klik tombol “Publikasikan”.

- Silahkan lihat blog anda dengan klik tombol “Lihat Blog”

- Selesai.

Cara Membuat Email di G-Mail Terbaru

2. Silahkan klik tautan ini https://accounts.google.com/

3. Lihat pojok kanan atas, klik CREATE AN ACCOUNT atau sesuaikan dengan bahasa yang anda gunakan.

4. Pada halaman berikutnya anda dihadapakan pada formulir pendaftaran email.

5. Pada kotak isian pertama isikan nama email yang anda inginkan. Jika terdapat keterangan bahwa email tersebut tidak tersedia, maka anda harus menggantinya dengan nama yang lain. Di sana telah disediakan rekomendasi nama email yang bisa anda gunakan.

6. Kotak isian dibawahnya isikan password yang anda inginkan, minimal 8 karakter. Di sana ada 2 kotak isian pasworrd untuk anda isi semuanya. Ada baiknya password anda tulis terlebih dahulu pada office word atau notepad lalu anda simpan dikomputer anda. Tetapi jika anda di warnet bisa anda simpan diflasdisc. Baru setelah itu anda copy dan pastekan pada kotak isian pasword pertama dan ke-2.

TIPS: Buatlah pasword dengan variasi angka huruf maupun lambang. Misal : 4KLjg_jhkG.

7. Isi negara anda, lalu isi juga kode chaptca yang tampak. Selanjtunya klik NEXT.

8. Anda akan di bawa ke halaman baru, klik Continue to Gmail.

9. Gmail anda sudah jadi, di sana akan terdapat Inbox dari tem Gmail.

Mudah bukan? Simpan nama email dan passwordnya dikomputer anda agar jika suatu saat lupa anda dapat membukanya kembali.

Andragogy: what is it and does it help thinking about adult learning?

Andragogy: what is it and does it help thinking about adult learning? The notion of andragogy has been around for nearly two centuries. It became particularly popular in North America and Britain as a way of describing adult learning through the work of Malcolm Knowles. But what actually does it mean, and how useful a term is it when thinking about adult learning?

Contents: introduction · some general issues with Knowles’ approach · the assumptions explored · andragogy and pedagogy · andragogy – the continuing debate · further reading and references · how to cite this article. See, also: malcolm knowles, informal adult education, self-direction and andragogyThe term andragogy was originally formulated by a German teacher, Alexander Kapp, in 1833 (Nottingham Andragogy Group 1983: v). He used it to describe elements of Plato’s education theory. Andragogy (andr- meaning ‘man’) could be contrasted with pedagogy (paid- meaning ‘child’ and agogos meaning ‘leading’) (see Davenport 1993: 114). Kapp’s use of andragogy had some currency but it was disputed, and fell into disuse. It reappeared in 1921 in a report by Rosenstock in which he argued that ‘adult education required special teachers, methods and philosophy, and he used the term andragogy to refer collectively to these special requirements’ (Nottingham Andragogy Group 1983: v). Eduard Lindeman was the first writer in English to pick up on Rosenstock’s use of the term. The he only used it on two occasions. As Stewart, his biographer, comments, ‘the new term seems to have impressed itself upon no one, not even its originators’. That may have been the case in North America, but in France, Yugoslavia and Holland the term was being used extensively ‘to refer to the discipline which studies the adult education process or the science of adult education’ (Nottingham Andragogy Group 1983: v).

In the minds of many around the adult education field, andragogy and the name of Malcolm Knowles have become inextricably linked. For Knowles, andragogy is premised on at least four crucial assumptions about the characteristics of adult learners that are different from the assumptions about child learners on which traditional pedagogy is premised. A fifth was added later.

1. Self-concept: As a person matures his self concept moves from one of being a dependent personality toward one of being a self-directed human being

2. Experience: As a person matures he accumulates a growing reservoir of experience that becomes an increasing resource for learning.

3. Readiness to learn. As a person matures his readiness to learn becomes oriented increasingly to the developmental tasks of his social roles.

4. Orientation to learning. As a person matures his time perspective changes from one of postponed application of knowledge to immediacy of application, and accordingly his orientation toward learning shifts from one of subject-centeredness to one of problem centredness.

5. Motivation to learn: As a person matures the motivation to learn is internal (Knowles 1984:12).Each of these assertions and the claims of difference between andragogy and pedagogy are the subject of considerable debate. Useful critiques of the notion can be found in Davenport (1993) Jarvis (1977a) Tennant (1996) (see below). Here I want to make some general comments about Knowles’ approach.

Some general issues with Knowles’ approach

First, as Merriam and Caffarella (1991: 249) have pointed out, Knowles’ conception of andragogy is an attempt to build a comprehensive theory (or model) of adult learning that is anchored in the characteristics of adult learners. Cross (1981: 248) also uses such perceived characteristics in a more limited attempt to offer a ‘framework for thinking about what and how adults learn’. Such approaches may be contrasted with those that focus on:- an adult’s life situation (e.g. Knox 1986; Jarvis 1987a);

- changes in consciousness (e.g. Mezirow 1983; 1990 or Freire 1972) (Merriam and Caffarella 1991).

Third, it is not clear whether this is a theory or set of assumptions about learning, or a theory or model of teaching (Hartree 1984). We can see something of this in relation to the way he has defined andragogy as the art and science of helping adults learn as against pedagogy as the art and science of teaching children. There is an inconsistency here.

Hartree (1984) raises a further problem. Has Knowles provided us with a theory or a set of guidelines for practice? The assumptions ‘can be read as descriptions of the adult learner… or as prescriptive statements about what the adult learner should be like’ (Hartree 1984 quoted in Merriam and Caffarella 1991: 250). This links with the point made by Tennant – there seems to be a failure to set and interrogate these ideas within a coherent and consistent conceptual framework. As Jarvis (1987b) comments, throughout his writings there is a propensity to list characteristics of a phenomenon without interrogating the literature of the arena (e.g. as in the case of andragogy) or looking through the lens of a coherent conceptual system. Undoubtedly he had a number of important insights, but because they are not tempered by thorough analysis, they were a hostage to fortune – they could be taken up in an ahistorical or atheoretical way.

The assumptions explored

With these things in mind we can look at the assumptions that Knowles makes about adult learners:1. Self-concept: As a person matures his self concept moves from one of being a dependent personality toward one of being a self-directed human being.The point at which a person becomes an adult, according to Knowles, psychologically, ‘is that point at which he perceives himself to be wholly self-directing. And at that point he also experiences a deep need to be perceived by others as being self-directing’ (Knowles 1983: 56). As Brookfield (1986) points out, there is some confusion as to whether self-direction is meant here by Knowles to be an empirically verifiable indicator of adulthood. He does say explicitly that it is an assumption. However, there are some other immediate problems:

- both Erikson and Piaget have argued that there are some elements of self-directedness in children’s learning (Brookfield 1986: 93). Children are not dependent learners for much of the time, ‘quite the contrary, learning for them is an activity which is natural and spontaneous’ (Tennant 1988: 21). It may be that Knowles was using ‘self-direction’ in a particular way here or needed to ask a further question – ‘dependent or independent with respect to what?’

- the concept is culturally bound – it arises out of a particular (humanist) discourse about the self which is largely North American in its expression. This was looked at last week – and will be returned to in future weeks.

A second aspect here is whether children’s and young people’s experiences are any less real or less rich than those of adults. They may not have the accumulation of so many years, but the experiences they have are no less consuming, and still have to be returned to, entertained, and made sense of. Does the fact that they have ‘less’ supposed experience make any significant difference to the process? A reading of Dewey (1933) and the literature on reflection (e.g. Boud et al 1985) would support the argument that age and amount of experience makes no educational difference. If this is correct, then the case for the distinctiveness of adult learning is seriously damaged. This is of fundamental significance if, as Brookfield (1986: 98) suggests, this second assumption of andragogy ‘can arguably lay claim to be viewed as a “given” in the literature of adult learning’.

3. Readiness to learn. As a person matures his readiness to learn becomes oriented increasingly to the developmental tasks of his social roles. As Tennant (1988: 21-22) puts it, ‘it is difficult to see how this assumption has any implication at all for the process of learning, let alone how this process should be differentially applied to adults and children’. Children also have to perform social roles.

Knowles does, however, make some important points at this point about ‘teachable’ moments. The relevance of study or education becomes clear as it is needed to carry out a particular task. At this point more ground can be made as the subject seems relevant.

However, there are other problems. These appear when he goes on to discuss the implications of the assumption. ‘Adult education programs, therefore, should be organised around ‘life application’ categories and sequenced according to learners readiness to learn’ (1980: 44)

First, as Brookfield comments, these two assumptions can easily lead to a technological interpretation of learning that is highly reductionist. By this he means that things can become rather instrumental and move in the direction of competencies. Language like ‘life application’ categories reeks of skill-based models – where learning is reduced to a series of objectives and steps (a product orientation). We learn things that are useful rather than interesting or intriguing or because something fills us with awe. It also thoroughly underestimates just how much we learn for the pleasure it brings (see below).

Second, as Humphries (1988) has suggested, the way he treats social roles – as worker, as mother, as friend, and so on, takes as given the legitimacy of existing social relationships. In other words, there is a deep danger of reproducing oppressive forms.

4. Orientation to learning. As a person matures his time perspective changes from one of postponed application of knowledge to immediacy of application, and accordingly his orientation toward learning shifts from one of subject-centeredness to one of problem centredness. This is not something that Knowles sees as ‘natural’ but rather it is conditioned (1984: 11). It follows from this that if young children were not conditioned to be subject-centred then they would be problem-centred in their approach to learning. This has been very much the concern of progressives such as Dewey. The question here does not relate to age or maturity but to what may make for effective teaching. We also need to note here the assumption that adults have a greater wish for immediacy of application. Tennant (1988: 22) suggests that a reverse argument can be made for adults being better able to tolerate the postponed application of knowledge.

Last, Brookfield argues that the focus on competence and on ‘problem-centredness’ in Assumptions 3 and 4 undervalues the large amount of learning undertaken by adults for its innate fascination. ‘[M]uch of adults’ most joyful and personally meaningful learning is undertaken with no specific goal in mind. It is unrelated to life tasks and instead represents a means by which adults can define themselves’ (Brookfield 1986: 99).

5. Motivation to learn: As a person matures the motivation to learn is internal (Knowles 1984:12). Again, Knowles does not see this as something ‘natural’ but as conditioned – in particular, through schooling. This assumption sits awkwardly with the view that adults’ readiness to learn is ‘the result of the need to perform (externally imposed) social roles and that adults have a problem-centred (utilitarian) approach to learning’ (Tennant 1988: 23).

In sum it could be said that these assumptions tend to focus on age and stage of development. As Ann Hanson (1996: 102) has argued, this has been at the expense of questions of purpose, or of the relationship between individual and society

Andragogy and pedagogy

As we compare Knowles’ versions of pedagogy and andragogy what we can see is a mirroring of the difference between what is known as the romantic and the classical curriculum (although this is confused by the introduction of behaviourist elements such as the learning contract). As Jarvis (1985) puts it, perhaps even more significantly is that for Knowles ‘education from above’ is pedagogy, while ‘education of equals’ is andragogy. As a result, the contrasts drawn are rather crude and do not reflect debates within the literature of curriculum and pedagogy.A comparison of the assumptions of pedagogy and andragogy following Knowles (Jarvis 1985: 51)

| Pedagogy | Andragogy | |

| The learner | Dependent. Teacher directs what, when, how a subject is learned and tests that it has been learned | Moves towards independence. Self-directing. Teacher encourages and nurtures this movement |

| The learner’s experience | Of little worth. Hence teaching methods are didactic | A rich resource for learning. Hence teaching methods include discussion, problem-solving etc. |

| Readiness to learn | People learn what society expects them to. So that the curriculum is standardized. | People learn what they need to know, so that learning programmes organised around life application. |

| Orientation to learning | Acquisition of subject matter. Curriculum organized by subjects. | Learning experiences should be based around experiences, since people are performance centred in their learning |

- the transmission of knowledge,

- product

- process, and

- praxis.

Andragogy – the continuing debate

By 1984 Knowles had altered his position on the distinction between pedagogy and andragogy. The child-adult dichotomy became less marked. He claimed, as above, that pedagogy was a content model and andragogy a process model but the same criticisms apply concerning his introduction of behaviourist elements. He even added the fifth assumption: As a person matures the motivation to learn is internal (1984: 12). Yet while there have been these shifts, the tenor of his work, as Jarvis (1987b) argues, still seems to suggest that andragogy is related to adult learning and pedagogy to child learning.There are those, like Davenport (1993) or the Nottingham Andragogy Group (1983) who believe it is possible to breathe life into the notion of andragogy – but they tend to founder on the same point. Kidd, in his study of how adults learn said the following:

[W]hat we describe as adult learning is not a different kind or order from child learning. Indeed our main point is that man must be seen as a whole, in his lifelong development. Principles of learning will apply, in ways that we shall suggest to all stages in life. The reason why we specify adults throughout is obvious. This is the field that has been neglected, not that of childhood. (Kidd 1978: 17)If Kidd is correct then the search for andragogy is pointless. There is no basis in the characteristics of adult learners upon which to construct a comprehensive theory. Andragogy can be seen as an idea that gained popularity in at a particular moment – and its popularity probably says more about the ideological times (Jarvis 1995: 93) than it does about learning processes.

Further reading and references

Here I have listed the main texts proposing ‘andragogy’ – and inevitably it is the work of Malcolm Knowles that features.Knowles, M. (1980) The Modern Practice of Adult Education. From pedagogy to andragogy (2nd edn). Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall/Cambridge. 400 pages. Famous as a revised edition of Knowles’ statement of andragogy – however, there is relatively little sustained exploration of the notion. In many respects a ‘principles and practice text’. Part one deals with the emerging role and technology of adult education (the nature of modern practice, the role and mission of the adult educator, the nature of andragogy). Part 2 deals organizing and administering comprehensive programmes (climate and structure in the organization, assessing needs and interests, defining purpose and objectives, program design, operating programs, evaluation). Part three is entitled ‘helping adults learn and consists of a chapter concerning designing and managing learning activities. There are around 150 pages of appendices containing various exhibits – statements of purpose, evaluation materials, definitions of andragogy.

Knowles, M. et al (1984) Andragogy in Action. Applying modern principles of adult education, San Francisco: Jossey Bass. A collection of chapters examining different aspects of Knowles’ formulation.

Knowles, M. S. (1990) The Adult Learner. A neglected species (4e), Houston: Gulf Publishing. First appeared in 1973. 292 + viii pages. Surveys learning theory, andragogy and human resource development (HRD). The section on andragogy has some reflection on the debates concerning andragogy. Extensive appendices which includes planning checklists,policy statements and some articles by Knowles – creating lifelong learning communities, from teacher to facilitator etc.

Nottingham Andragogy Group (1983) Towards a Developmental Theory of Andragogy, Nottingham: University of Nottingham Department of Adult Education. 48 pages. Brief review of the andragogy debate to that date. Section 1 deals with adult development; section 2 with the empirical and theoretical foundations for a theory of andragogy; and section 3 proposes a model and theory.

Some critiques of the notion of andragogy – and more particularly the work of Knowles can be found in:

Davenport (1993) ‘Is there any way out of the andragogy mess?’ in M. Thorpe, R. Edwards and A. Hanson (eds.) Culture and Processes of Adult Learning, London; Routledge. (First published 1987).

Jarvis, P. (1987a) ‘Malcolm Knowles’ in P. Jarvis (ed.) Twentieth Century Thinkers in Adult Education, London: Croom Helm.

Tennant, M. (1988, 1996) Psychology and Adult Learning, London: Routledge.

Other references

Boud, D. et al (1985) Reflection. Turning experience into learning, London: Kogan Page.Brookfield, S. D. (1986) Understanding and Facilitating Adult Learning. A comprehensive analysis of principles and effective practice, Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Cross, K. P. (1981) Adults as Learners. Increasing participation and facilitating learning (1992 edn.), San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Dewey, J. (1933) How We Think, New York: D. C. Heath.

Hanson, A. (1996) ‘The search for separate theories of adult learning: does anyone really need andragogy?’ in Edwards, R., Hanson, A., and Raggatt, P. (eds.) Boundaries of Adult Learning. Adult Learners, Education and Training Vol. 1, London: Routledge.

Humphries, B. (1988) ‘Adult learning in social work education: towards liberation or domestication’. Critical Social Policy No. 23 pp.4-21.

Jarvis, P. (1985) The Sociology of Adult and Continuing Education, Beckenham: Croom Helm.

Kidd, J. R. (1978) How Adults Learn (3rd. edn.),Englewood Cliffs, N.J.:Prentice Hall Regents.

Kliebart, H. M. (1987) The Struggle for the American Curriculum 1893-1958, New York : Routledge.

Merriam, S. B. and Caffarella, R. S. (1991)Learning in Adulthood. A comprehensive guide, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Acknowledgement: The picture ‘Ari is facilitating’ was taken by Shira Golding and is reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 2.0 Generic licence. It can be found on Flickr.com: http://www.flickr.com/photos/boojee/2668136741/.

How to cite this article: Smith, M. K. (1996; 1999, 2010) ‘Andragogy’, the encyclopaedia of informal education. [http://infed.org/mobi/andragogy-what-is-it-and-does-it-help-thinking-about-adult-learning/. Retrieved: insert date]

© Mark K. Smith 1996, 1999, 2010

What Is Adult Education?

What is adult education?

What is adult education? Is adult education a practice or a program? A methodology or an organization? A ‘science’ or a system? A process or a profession?

Is adult education a practice or a program? A methodology or an organization? A ‘science’ or a system? A process or a profession? Is adult education different from continuing education, vocational education, higher education? Does adult education have form and substance, or does it merely permeate through the environment like air? Is adult education, therefore, everywhere and yet nowhere in particular? Does adult education even exist? (McCullough 1980 quoted in Jarvis 1987a: 3)Just how are we to approach adult education if it is everywhere and nowhere? As a starting point, Courtney (1989: 17-23) suggests that we can explore it from five basic and overlapping perspectives. Adult education as:

- the work of certain institutions and organizations. What we know as adult education has been shaped by the activities of key organizations. Adult education is, thus, simply what certain organizations such as the Workers Education Association or the YMCA do.

- a special kind of relationship. One way to approach this is to contrast adult education with the sort of learning that we engage in as part of everyday living. Adult education could be then seen as, for example, the process of managing the external conditions that facilitate the internal change in adults called learning (see Brookfield 1986: 46). In other words, it is a relationship that involves a conscious effort to learn something.

- a profession or scientific discipline. Here the focus has been on two attributes of professions: an emphasis on training or preparation, and the notion of a specialized body of knowledge underpinning training and preparation. According to this view ‘the way in which adults are encouraged to learn and aided in that learning is the single most significant ingredient of adult education as a profession’ (op cit: 20).

- stemming from a historical identification with spontaneous social movements. Adult education can be approached as a quality emerging through the developing activities of unionism, political parties and social movements such as the women’s movement and anti-colonial movements (see Lovett 1988).

- distinct from other kinds of education by its goals and functions. This is arguably the most common way of demarcating adult education from other forms of education. For example:

Adult education is concerned not with preparing people for life, but rather with helping people to live more successfully. Thus if there is to be an overarching function of the adult education enterprise, it is to assist adults to increase competence, or negotiate transitions, in their social roles (worker, parent, retiree etc.), to help them gain greater fulfilment in their personal lives, and to assist them in solving personal and community problems. (Darkenwald and Merriam 1982: 9)Darkenwald and Merriam combine three elements. Adult education is work with adults, to promote learning for adulthood. Approached via an interest in goals, ‘adult’ education could involve work with children so that they may become adult. As Lindeman (1926: 4) put it: ‘This new venture is called adult education not because it is confined to adults but because adulthood, maturity, defines its limits’.

The meaning of ‘adult’

A further issue is the various meanings given to ‘adult’. We might approach the notion, for example,as a:- biological state (post-puberty),

- legal state (aged 18 or over; aged 21 or over?),

- psychological state (their ‘self concept’ is that of an ‘adult’)

- form of behaviour (adulthood as being in touch with one’s capacities whatever the context)

- set of social roles (adulthood as the performance of certain roles e.g. working, raising children etc.).

A working definition

Most current texts seem to approach adult education via the adult status of students, and a concern with education (creating enlivening environments for learning). We could choose a starting definition from a range of writers. Rather than muck around I have taken one advanced by Sharan B. Merriam and Ralph G. Brockett (1997: 8). They define adult education as:activities intentionally designed for the purpose of bringing about learning among those whose age, social roles, or self-perception define them as adults.This definition has the virtue of side-stepping some of the issues around the meaning of ‘adult’ – but doesn’t fully engage with the nature of education. However, it is a start.

Further reading and references

Brookfield, S. D. (1986) Understanding and Facilitating Adult Learning. A comprehensive analysis of principles and effective practices, Milton Keynes: Open University Press.Collins, M. (1991) Adult Education as Vocation. A critical role for the adult educator, London: Routledge.

Courtney, S. (1989) ‘Defining adult and continuing education’ in S. B. Merriam and P. M. Cunningham (eds.) Handbook of Adult and Continuing Education, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Darkenwald, G. G. and Merriam, S. B. (1982) Adult Education. Foundations of practice, New York: Harper and Row.

Jarvis, P. (1987) Adult Learning in the Social Context, Beckenham: Croom Helm.

Jarvis, P. (1995) Adult and Continuing Education. Theory and practice, (2nd. edn.), London: Routledge. Lovett, T. (ed.) (1988) Radical Approaches to Adult Education: a reader, Beckenham: Croom Helm

Lindeman, E. C. (1926) The Meaning of Adult Education (1989 edn), Norman: University of Oklahoma.

McCullough, K. O. (1980) ‘Analyzing the evolving structure of adult education’ in J. Peters (ed.) Building an Effective Adult Education Enterprise, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Merriam, S. B. and Brockett, R. G. (1996) The Profession and Practice of Adult Education, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Paterson, R. W. K. (1979) Values, Education and the Adult. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Squires, G. (1993) ‘Education for adults’ in M. Thorpe, R. Edwards and A. Hanson (eds.) Culture and Processes of Adult Learning, London: Routledge.

Stephens, M. D. (1990) Adult Education, London: Cassell.

Acknowledgement: Picture: ‘Adult education’ by Adam Kuban. Sourced from flickr and reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) licence. http://www.flickr.com/photos/slice/3178384510/

© Mark K. Smith 1996, 1999.

Julius Nyerere, Lifelong Learning and Education

Julius Nyerere, lifelong learning and education

Julius Nyerere, lifelong learning and education. One of Africa’s most respected figures, Julius Nyerere (1922 – 1999) was a politician of principle and intelligence. Known as Mwalimu or teacher he had a vision of education and social action that was rich with possibility.

contents: introduction · ujamma, socialism and self reliance · education for self-reliance · adult education, lifelong learning and learning for liberation · liberation struggles · retirement · further reading and referencesJulius Kambarage Nyerere was born on April 13, 1922 in Butiama, on the eastern shore of lake Victoria in north west Tanganyika. His father was the chief of the small Zanaki tribe. He was 12 before he started school (he had to walk 26 miles to Musoma to do so). Later, he transferred for his secondary education to the Tabora Government Secondary School. His intelligence was quickly recognized by the Roman Catholic fathers who taught him. He went on, with their help, to train as a teacher at Makerere University in Kampala (Uganda). On gaining his Certificate, he taught for three years and then went on a government scholarship to study history and political economy for his Master of Arts at the University of Edinburgh (he was the first Tanzanian to study at a British university and only the second to gain a university degree outside Africa. In Edinburgh, partly through his encounter with Fabian thinking, Nyerere began to develop his particular vision of connecting socialism with African communal living.

On his return to Tanganyika, Nyerere was forced by the colonial authorities to make a choice between his political activities and his teaching. He was reported as saying that he was a schoolmaster by choice and a politician by accident. Working to bring a number of different nationalist factions into one grouping he achieved this in 1954 with the formation of TANU (the Tanganyika African National Union). He became President of the Union (a post he held until 1977), entered the Legislative Council in 1958 and became chief minister in 1960. A year later Tanganyika was granted internal self-government and Nyerere became premier. Full independence came in December 1961 and he was elected President in 1962.

Nyerere’s integrity, ability as a political orator and organizer, and readiness to work with different groupings was a significant factor in independence being achieved without bloodshed. In this he was helped by the co-operative attitude of the last British governor – Sir Richard Turnbull. In 1964, following a coup in Zanzibar (and an attempted coup in Tanganyika itself) Nyerere negotiated with the new leaders in Zanzibar and agreed to absorb them into the union government. The result was the creation of the Republic of Tanzania.

Ujamma, socialism and self reliance

As President, Nyerere had to steer a difficult course. By the late 1960s Tanzania was one of the world’s poorest countries. Like many others it was suffering from a severe foreign debt burden, a decrease in foreign aid, and a fall in the price of commodities. His solution, the collectivization of agriculture, villigization (see Ujamma below) and large-scale nationalization was a unique blend of socialism and communal life. The vision was set out in the Arusha Declaration of 1967 (reprinted in Nyerere 1968):The objective of socialism in the United Republic of Tanzania is to build a society in which all members have equal rights and equal opportunities; in which all can live in peace with their neighbours without suffering or imposing injustice, being exploited, or exploiting; and in which all have a gradually increasing basic level of material welfare before any individual lives in luxury. (Nyerere 1968: 340)The focus, given the nature of Tanzanian society, was on rural development. People were encouraged (sometimes forced) to live and work on a co-operative basis in organized villages or ujamaa (meaning ‘familyhood’ in Kishwahili). The idea was to extend traditional values and responsibilities around kinship to Tanzania as a whole.

Julius Nyerere on the Arusha Declaration

The policy met with significant political resistance (especially when people were forced into rural communes) and little economic success. Nearly 10 million peasants were moved and many were effectively forced to give up their land. The idea of collective farming was less than attractive to many peasants. A large number found themselves worse off. Productivity went down. However, the focus on human development and self-reliance did bring some success in other areas notably in health, education and in political identity.

Education for self-reliance

As Yusuf Kassam (1995: 250) has noted, Nyerere’s educational philosophy can be approached under two main headings: education for self-reliance; and adult education, lifelong learning and education for liberation. His interest in self-reliance shares a great deal with Gandhi’s approach. There was a strong concern to counteract the colonialist assumptions and practices of the dominant, formal means of education. He saw it as enslaving and oriented to ‘western’ interests and norms. Kassim (1995: 251) sums up his critique of the Tanzanian (and other former colonies) education system as follows:- Formal education is basically elitist in nature, catering to the needs and interests of the very small proportion of those who manage to enter the hierarchical pyramid of formal schooling: ‘We have not until now questioned the basic system of education which we took over at the time of Independence. We have never done that because we have never thought about education except in terms of obtaining teachers, engineers, administrators, etc. Individually and collectively we have in practice thought of education as a training for the skills required to earn high salaries in the modern sector of our economy’ (Nyerere, 1968 267).

- The education system divorces its participants from the society for which they are supposed to be trained.

- The system breeds the notion that education is synonymous with formal schooling, and people are judged and employed on the basis of their ability to pass examinations and acquire paper qualifications.

- The system does not involve its students in productive work. Such a situation deprives society of their much-needed contribution to the increase in national economic output and also breeds among the students a contempt for manual work. (Kassam 1995: 251)

- It should be oriented to rural life.

- Teachers and students should engage together in productive activities and students should participate in the planning and decision-making process of organizing these activities.

- Productive work should become an integral part of the school curriculum and provide meaningful learning experience through the integration of theory and practice.

- The importance of examinations should be downgraded.

- Children should begin school at age 7 so that they would be old enough and sufficiently mature to engage in self-reliant and productive work when they leave school.

- Primary education should be complete in itself rather than merely serving as a means to higher education.

- Students should become self-confident and co-operative, and develop critical and inquiring minds. (summarized in Kassam 1995: 253

Adult education, lifelong learning and learning for liberation

In the Declaration of Dar es Salaam Julius Nyerere made a ringing call for adult education to be directed at helping people to help themselves and for it to approached as part of life: ‘integrated with life and inseparable from it’. For him adult education had two functions. To:- Inspire both a desire for change, and an understanding that change is possible.

- Help people to make their own decisions, and to implement those decisions for themselves. (Nyerere 1978: 29, 30)

Julius Nyerere – The Declaration of Dar – es – Salaam

- generalists like community development workers, political activists and religious teachers. Such people are not politically neutral, they will affect how people look at the society in which they live, and how they seek to use it or change it. (ibid.: 31)

- specialists like those concerned with health, agriculture, child care, management and literacy.

In terms of method, two aspects stand out:

- Educators do not give to another something they possess. Rather, they help learners to develop their own potential and capacity.

- Those that educators work with have experience and knowledge about the subjects they are interested in – although they may not realize it.

The teacher of adults is , for Nyerere, a leader – ‘a guide along a path which all will travel together’ (ibid.: 34).[B]y drawing out the things the learner already knows, and showing their relevance to the new thing which has to be learnt, the teacher has done three things. He has built up the self-confidence of the man who wants to learn, by showing him that he is capable of contributing. He has demonstrated the relevance of experience and observation as a method of learning when combined with thought and analysis. And he ha shown what I might call the “mutuality” of learning—that is, that by sharing our knowledge we extend the totality of our understanding and our control over our lives. (1978: 33)

In practical terms this approach proved successful. Mass literacy campaigns were initiated and carried through (for example, between 1975 and 1977 illiteracy fell from 39 to 27 per cent – by 1986 it was at 9.6 per cent); and various health and agricultural programmes were mounted e.g the ‘Man is Health’ campaign in 1973, and ‘Food is Life’ (1975) (Mushi and Bwatwa 1998). Adult education initiatives have made a significant contribution to mobilising people for development (Kassam 1979).

Liberation struggles

A committed pan-Africanist, Nyerere provided a home for a number of African liberation movements including the African National Congress (ANC) and the Pan African Congress (PAC) of South Africa, Frelimo when seeking to overthrow Portuguese rule in Mozambique, Zanla (and Robert Mugabe) in their struggle to unseat the white regime in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). He also opposed the brutal regime of Idi Amin in Uganda. Following a border invasion by Amin in 1978, a 20,000-strong Tanzanian army along with rebel groups, invaded Uganda. It took the capital, Kampala, in 1979, restoring Uganda’s first President, Milton Obote, to power. The battle against Amin was expensive and placed a strain on government finances. There was considerable criticism within Tanzania that he had both overlooked domestic issues and had not paid proper attention to internal human rights abuses. Tanzania was a one party state – and while there was a strong democratic element in organization and a concern for consensus, this did not stop Nyerere using the Preventive Detention Act to imprison opponents. In part this may have been justified by the need to contain divisiveness, but there does appear to have been a disjuncture between his commitment to human rights on the world stage, and his actions at home.Retirement

In 1985 Nyerere gave up the Presidency but remained as chair of the Party – Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM). He gradually withdrew from active politics, retiring to his farm in Butiama. In 1990 he relinquished his chairmanship of CCM but remained active on the world stage as Chair of the Intergovernmental South Centre. One of his last high profile actions was as the chief mediator in the Burundi conflict (in 1996). He died in a London hospital of leukaemia on October 14, 1999.Tom Porteous, writing in The Independent (October 15, 1999) summed him up as follows:

Slight in build, somewhat austere in manner, Nyerere was neither vain nor arrogant. He set great store by honesty and sincerity. A family man devoted to his wife and children, he was extremely loyal to his friends – sometimes to a fault. He inspired among his people both devotion and respect and returned the compliment by complete dedication to his work on their behalf as head of state. He was ready to admit his mistakes, and to show flexibility and pragmatism, but never if this meant compromising his cherished Catholic, humanist and socialist ideals.

Nyerere’s life and career are an inspiration to the many Africans who dismiss the notion current in elite African circles today that justice, dignity and freedom should be subordinated to the single-minded pursuit of prosperity through economic liberalisation and structural adjustment. Africa needs more leaders of Nyerere’s quality, integrity and wisdom.

Further reading and references

Books by Julius Nyerere:

Nyerere, J. (1968) Freedom and Socialism. A Selection from Writings & Speeches, 1965-1967, Dar es Salaam: Oxford University Press. This book includes The Arusha Declaration; Education for self-reliance; The varied paths to socialism; The purpose is man; and socialism and development.Nyerere, J. (1974) Freedom & Development, Uhuru Na Maendeleo, Dar es Salaam: Oxford University Press. Includes essays on adult education; freedom and development; relevance; and ten years after independence.

Nyerere, J. (1977) Ujamaa-Essays on Socialism, London: Oxford University Press.

Nyerere, J. (1979) Crusade for Liberation, Dar es Salaam: Oxford University Press.

See, also:

Nyerere, J. (1978) ‘”Development is for Man, by Man, and of Man”: The Declaration of Dar es Salaam’ in B. Hall and J. R. Kidd (eds.) Adult Learning: A design for action, Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Material on Julius Nyerere:

Assensoh, A. B. (1998) African Political Leadership: Jomo Kenyatta, Kwame Nkrumah, and Julius K. Nyerere, New York: Krieger Publishing Co.Kassam, Y. (1995) ‘Julius Nyerere’ in Z. Morsy (ed.) Thinkers on Education, Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

Legum, C. and Mmari, G. (ed.) (1995) Mwalimu : The Influence of Nyerere, London: Africa World Press.

Samoff, J. (1990) ‘”Modernizing” a socialist vision: education in Tanzania’, in M. Carnoy and J. Samoff (eds.) Education and Social Transition in the Third World, Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

Other references

Hinzen, H. and Hundsdorfer, V. H. (eds.) (1979) The Tanzanian Experience. Education for liberation and development, Hamburg: UNESCO Institute for Education.Kassam, Y. (1978) The Adult Education Revolution in Tanzania, Nairobi: Shungwaya Publishers.

Mushi, P. A. K. and Bwatwa, Y. D. M. (1998) ‘Tanzania’ in J. Draper (ed.) Africa Adult Education. Chronologies in Commonwealth cultures, Leicester: NIACE.

Acknowledgement: Picture: Julius Kambarage Nyerere, leader of the Elected Members in Tanganyika’s Legislative Council and President of the territory’s largest political party, the Tanganyika African National Union. The National Archives UK. Licensed under the Open Government Licence v1.0 and sourced from Wikimedia Commons.

© Mark K. Smith 1998.

The Theory and Rhetoric of the Learning Society

The theory and rhetoric of the learning society

The theory and rhetoric of the learning society. The idea of the learning society has featured strongly in recent pronouncements around adult and lifelong learning. But what actually is the learning society? How have notions of the learning society developed. We the theory and rhetoric of the learning society and provide an introductory guide and reading list.

Contents: introduction · the development of the idea of the learning society · current models of the learning society · conclusion · further reading and references · to cite this articleToday there is much talk of the learning organization, the knowledge economy and the like. The ‘learning society’ is an aspect of this movement to look beyond formal educational environments, and to locate learning as a quality not just of individuals but also as an element of systems (see the social/situational orientation to learning).Here we briefly examine the development of the notion and its current application. We suggest that when we strip away the rhetoric, the notion of the learning society may have utility as an aspirational and descriptive tool.

The development of the idea of the learning society

Notions of the learning society gained considerable currency in policy debates in a number of countries since the appearance of Learning to Be:If learning involves all of one’s life, in the sense of both time-span and diversity, and all of society, including its social and economic as well as its educational resources, then we must go even further than the necessary overhaul of ‘educational systems’ until we reach the stage of a learning society. (Faure et al 1972: xxxiii)The notion has subsequently been wrapped up with the emergence of so called ‘post-industrial’ or ‘post-Fordist’ societies and linked to other notions such as lifelong learning and ‘the learning organization’ (see, in particular, the seminal work or Argyris and Schon 1978). It is an extra-ordinarily elastic term that provides politicians and policymakers with something that can seem profound, but on close inspection is largely vacuous. All societies need to be charactized by learning or else they will die!

Donald Schon and the loss of the stable state. An early, defining, contribution was made by Donald Schon (1963, 1967, 1973). He provided a theoretical framework linking the experience of living in a situation of an increasing change with the need for learning.

The loss of the stable state means that our society and all of its institutions are in continuous processes of transformation. We cannot expect new stable states that will endure for our own lifetimes.One of Schon’s great innovations was to explore the extent to which companies, social movements and governments were learning systems – and how those systems could be enhanced. He suggests that the movement toward learning systems is, of necessity, ‘a groping and inductive process for which there is no adequate theoretical basis’ (ibid.: 57). The business firm, Donald Schon argued, was a striking example of a learning system. He charted how firms moved from being organized around products toward integration around ‘business systems’ (ibid.: 64). He made the case that many companies no longer have a stable base in the technologies of particular products or the systems build around them. Crucially Donald Schon then went on with Chris Argyris to develop a number of important concepts with regard to organizational learning. Of particular importance for later developments was their interest in feedback and single- and double-loop learning.

We must learn to understand, guide, influence and manage these transformations. We must make the capacity for undertaking them integral to ourselves and to our institutions.

We must, in other words, become adept at learning. We must become able not only to transform our institutions, in response to changing situations and requirements; we must invent and develop institutions which are ‘learning systems’, that is to say, systems capable of bringing about their own continuing transformation. (Schon 1973: 28)

However, as Griffin and Brownhill (2001) have pointed out three other earlier conceptions of the learning society also repay attention.

Robert M. Hutchins and the learning society. Hutchins, in a book first published in 1968, argued that a ‘learning society’ had become necessary. Education systems were no longer able to respond to the demands made upon them. Instead it was necessary to look toward the idea that learning was at the heart of change. ‘The two essential facts are… the increasing proportion of free time and the rapidity of change. The latter requires continuous education; the former makes it possible (1970: 130). He looked to ancient Athens for a model. There:

education was not a segregated activity, conducted for certain hours, in certain places, at a certain time of life. It was the aim of the society. The city educated the man. The Athenian was educated by culture, by paideia. (Hutchins 1970: 133)Slavery made this possible – releasing citizens to participate in the life of the city. Hutchins’ argument was that ‘machines can do for modern man what slavery did for the fortunate few in Athens’ (op. cit.).

Torsten Husén, technology and the learning society. Torsten Husén argued that it would be necessary for states to become ‘learning societies’ – where knowledge and information lay at the heart of their activities.

Among all the ‘explosions’ that have come into use as labels to describe rapidly changing Western society, the term ‘knowledge explosion’ is one of the most appropriate. Reference is often made to the ‘knowledge industry’, meaning both the producers of knowledge, such as research institutes, and its distributors, e.g. schools, mass media, book publishers, libraries and so on. What we have been witnessing since the mid-1960s in the field of distribution technology may well have begun to revolutionize the communication of knowledge within another ten years of so. (Husén 1974: 239)Husén’s approach was futurological (where Hutchins was essentially based on classical humanism). The organizing principles of Husén’s vision of a relevant educational system have been summarized by Stewart Ranson (1998) and included:

Education is going to be a lifelong process.Husén’s vision was based ‘upon projections from current trends in communications technology and the likely consequences of these for knowledge, information and production’ (Griffin and Brownhill 2001: 58. Significantly, these predictions have largely come true.

Education will not have any fixed points of entry and ‘cut-off’ exits. It will become a more continuous process within formal education and in its role within other functions of life.

Education will take on a more informal character as it becomes accessible to more and more individuals. In addition to ‘learning centers’, facilities will be provided for learning at home and at the workplace, for example by the provision of computer terminals.

Formal education will become more meaningful and relevant in its application.

‘To an ever-increasing extent, the education system will become dependent on large supporting organizations or supporting systems… to produce teaching aids, systems of information processing and multi-media instructional materials’ (Husén 1974: 198-9)

Roger Boshier, adult education and the learning society. Boshier argued for an integrated model of education that allowed for participation throughout a person’s lifetime. Influenced by more radical and democratic writers like Freire, Illich and Goodman, and his appreciation of economic and social change, Boshier looked to the democratic possibilities of a learning society.

When we turn to current explorations of the learning society it is possible to discern the various strands developed by these writers: technological, cultural and democratic. (The philosophical underpinning of these models is discussed by Griffin and Brownhill 2001). However, it is the technological that appears to have become dominant in many policy documents.

Current models of the learning society

The learning society can be approached as an aspiration and as a description (Hughes and Tight 1998: 184). It is seen as something that is required if states and regions are to remain competitive within an increasingly globalized economy. It may be sought after as a means of improving individual and communal well-being. Edwards (1997) has provided us with a helpful mapping of the territory. He identifies three key strands in discourses around the notion of a learning society in which there is a shift from a focus on the provision of learning opportunities to one on learning. The first is portrayed as a product of modernism, the third as exhibiting a typically post-modern orientation. The second strand, with its emphasis on markets, economic imperatives and individual achievement, he argues, currently dominates.Richard Edwards on learning society

[T]he function of the learning society myth is to provide a convenient and palatable rationale and packaging for the current and future policies of different power groups within society…. Nothing approaching a learning society currently exists, and there is no real practical prospect of one coming into existence in the foreseeable future.In Britain the notion of the learning society has certainly bitten deep into the rhetoric of policy makers – as the Green Paper The Learning Age (DFEE 1998) demonstrates – and highly instrumental and vocational understandings of education appear to predominate. There is relatively little talk of, or resources flowing into, more liberal and emancipatory educational processes (see, for example, social exclusion, ‘joined-up thinking’ and individualization – the connexions strategy). However, does this make a case for abandoning the notion of the learning society?

Yet this myth has power. [It] is a product of, and also embodies, earlier myths which link education, productivity and change. (Hughes and Tight 1998: 188)

Michael Strain and John Field (1998) have been critical of views like that put forward by Hughes and Tight. They argue that we should be too hasty in our rush to sideline the notion.

The project may indeed come to be subverted, hijacked by corporatist, instrumentalist, universalist interests embodied in national governments and globalized financial institutions (of which the World Bank is a signal example)… But democratic conditions still make possible a formative discourse from which much stands to be gained. We should not give up so easily and on such a superficial and limited critique. There is ‘out there’ a real society in which knowledge and other resources are unequally distributed, to a degree that is not only inimical to the fulfillment of individual capabilities and freedoms, but, arguably, detrimental to the collective survival and development of human society. (Strain and Field 1998: 240).In a similar fashion Stewart Ranson (1992, 1994, 1998) has argued that the notion of a learning society provides us with a helpful way of making sense of the shifts required in the context of the profound changes associated with globalization and other dynamics of social and economic change.

Conclusion

So what are we to do? It pays to approach the rhetoric of policy makers around the learning society and lifelong learning with skepticism. As Ranson (1998: 243) has commented: ‘There is a need for greater clarity in defining the meaning of the learning society, and for establishing criteria which allow some rather than all usages to be interpreted as legitimated’. The notion of the learning society may have some theoretical and analytical potential – but it does require considerable work if that potential is be realized.The strength of the idea of a learning society as a concept is that in linking learning explicitly to the idea of a future society, it provides the basis for a critique of the minimal learning demands of much work and other activities in our present society, not excluding the sector specializing in education. Its weakness is that so far the criteria for the critique remain very general and therefore, like many terms of contemporary educational discourse such as partnership and collaboration, it can take a variety of contradictory meanings. (Young 1998: 193)It is necessary to deepen our theorization of the relationship between education and economic life; to appreciate developments in our theorization of learning; and to draw upon understandings of human beings as active, and cooperative, agents if the notion of the learning society is to move beyond the level of rhetoric (or even myth). It may well be that, as Richard Edwards (1997) suggests, the idea of learning networks or webs (after Illich) may be a more appropriate and convivial way forward.

Further reading and references

Department for Education and Employment (1998) The Learning Age: A renaissance for a new Britain, London: The Stationery Office. Glossy Green Paper full of policy speak, that reveals the shift to individualized, market-driven notions of lifelong learning.Edwards, R. (1997) Changing Places? Flexibility, lifelong learning and a learning society, London: Routledge. 214 + x pages. Edwards looks at some of the key discourses that he claims have come to govern the education and training of adults. He looks at the context for such changes and their contested nature. The focus is on how the idea of a learning society has developed in recent years. The usual trip through postmodern thinking is followed by an analysis of the ways in which specific discourses of change have been constructed to provide the basis for a growing interest in lifelong learning and a learning society. Edwards also argues that there has been a shift in discourses from a focus on inputs, on adult education and provision toward one on outputs, on learning and the learner. This shift is linked to supporting access and flexibility. A further chapter examines ‘adult educators’ as reflective practitioners and as workers with vocation – and how they are being constructed as ‘enterprising workers’. The book finishes with a return to the notion of the learning society.

Faure, E. and others (1972) Learning to Be, Paris: UNESCO. 312 pages. Important and influential statement of the contribution that lifelong learning can make to human development. Argued that lifelong education should be ‘the maste concept for educational policies in the years to come for both developed and developing countries’ (p. 182). The first part of the book looks to the current state of education, part two looks at possible futures, and part three examines how a learning society might be achieved. The latter includes chapters in the role and function of educational strategies, elements for contemporary strategies, and roads to solidarity.

Jarvis, P. (ed.) (2001) The Age of Learning. Education and the knowledge society, London: Kogan Page. 229 pages. Collection of chapters that explores the emergence of the learning society; learning and the learning society; the mechanics of the learning society; the implications of the learning society; and reflections on the age of learning.

Raggett, P., Edwards, R. and Small, N. (1995) The Learning Society: Challenges and trends, London: Routledge. 302 + x pages. Examines the demographic, technical, economic and cultural changes that have led to an interest in a ‘learning society’. Produced for E827 (MA in Education). Useful collection of material.

Ranson, S. (ed.) (1998) Inside the Learning Society, London: Cassell. 294 + x pages. The introductory chapter explores the lineages of the learning society; part one of the book examines different perspectives on the learning society; part two, the learning society and public policy; part three, the critical debate; and a concluding chapter looks to the learning democracy. One of the best collections of material around the learning society.

References

Boshier, R. (ed.) (1980) Toward the Learning Society. New Zealand adult education in transition, Vancouver: Learning Press.Griffin, C. and Brownhill, R. (2001) ‘The learning society’ in P. Jarvis (ed.) The Age of Learning. Education and the knowledge society, London: Kogan Page.

Hughes, C. and Tight, M. (1995, 1998) ‘The myth of the learning society’, British Journal of Educational Studies 43(3): 290-304. Reprinted in S. Ranson (1998) Inside the Learning Society, London: Cassell. [The page numbers given in this text are from Ranson).

Husén, T. (1974) The Learning Society, London: Methuen.

Husén, T. (1986) The Learning Society Revisited, Oxford: Pergamon.

Hutchins, R. M. (1970) The Learning Society, Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Ranson, S. (1992) 'Towards the learning society', Educational Management and Administration 20(2): 68-79

Ranson, S. (1994) Towards the Learning Society, London: Cassell.

Ranson, S. (1998) 'A reply to my critics' in S. Ranson (1998) Inside the Learning Society, London: Cassell.

Schön, D. A. (1967) Invention and the evolution of ideas, London: Tavistock (first published in 1963 as Displacement of Concepts).

Schön, D. A. (1967) Technology and change : the new Heraclitus, Oxford: Pergamon.

Schön, D. A. (1973) Beyond the Stable State. Public and private learning in a changing society, Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Strain, M. and Field, J. (1997) 'On the myth of the learning society', British Journal of Educational Studies 45(2): 141-155. Reprinted in S. Ranson (1998) Inside the Learning Society, London: Cassell. [The page numbers given in this text are from Ranson).

Young, M. (1998) 'Post-compulsory education for a learning society' in S. Ranson (1998) Inside the Learning Society, London: Cassell.

Acknowledgement: Picture: Learning the imagination by Tony Hall. Sourced from Flick and reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-ND 2.0) licence. http://www.flickr.com/photos/anotherphotograph/4021347461/

To cite this article: Smith, M. K. (2000) 'The theory and rhetoric of the learning society', The encyclopedia of informal education. [http://infed.org/mobi/the-theory-and-rhetoric-of-the-learning-society/. Retrieved: insert date].

© Mark K. Smith 2000, 2002

.jpg)